I’m working on a very beautiful and meaningful short film right now, and the director and I are currently in the Terminology Tango: that careful dance you do as you’re going back and forth with new revisions and new requests, trying to understand each other while attempting to not tread on each other’s toes.

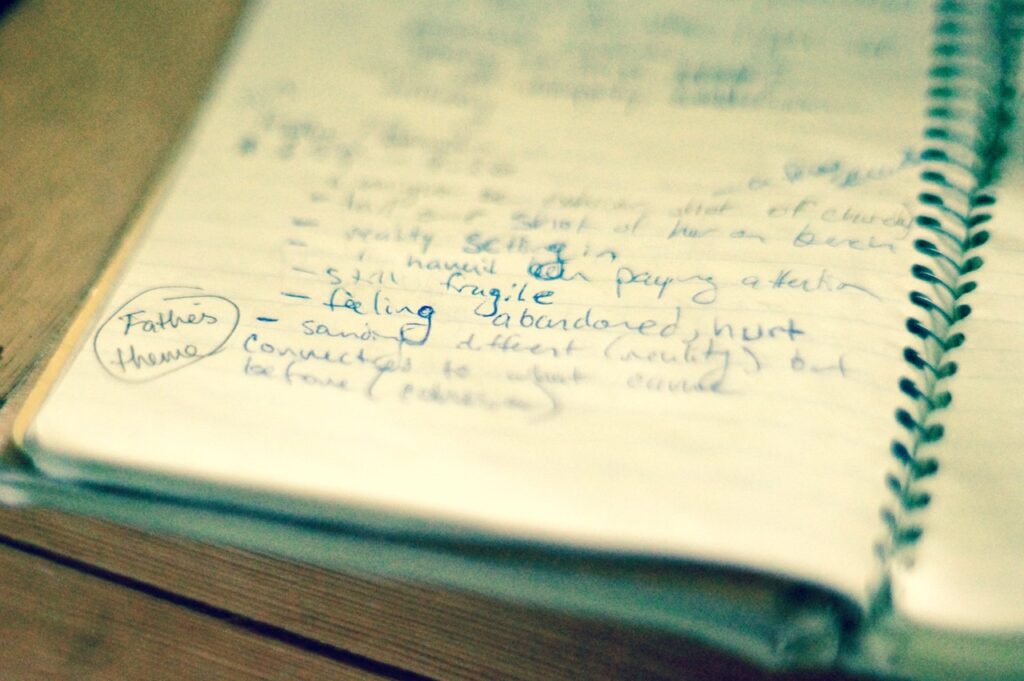

It may be a surprise to find out that I really, truly enjoy working with directors that don’t have any music knowledge. In fact, some of my best scores were produced for music-illiterate directors. It’s freeing to leave behind the technical engine of composition, and revel in what makes it beautiful and emotional. I don’t need someone to tell me the number of cadences I should use, or in which register to put the violins, in order to create a sentimental moment. Here’s what I do want to know:

- What are the emotions in the scene?

- What emotions are not in the scene, but you want the audience to be feeling?

- Whose point of view is the scene from?

- Do any characters have any desires? Are there any desires not being met?

- Where does this scene lead?

- How does this scene fit in the film as a while?

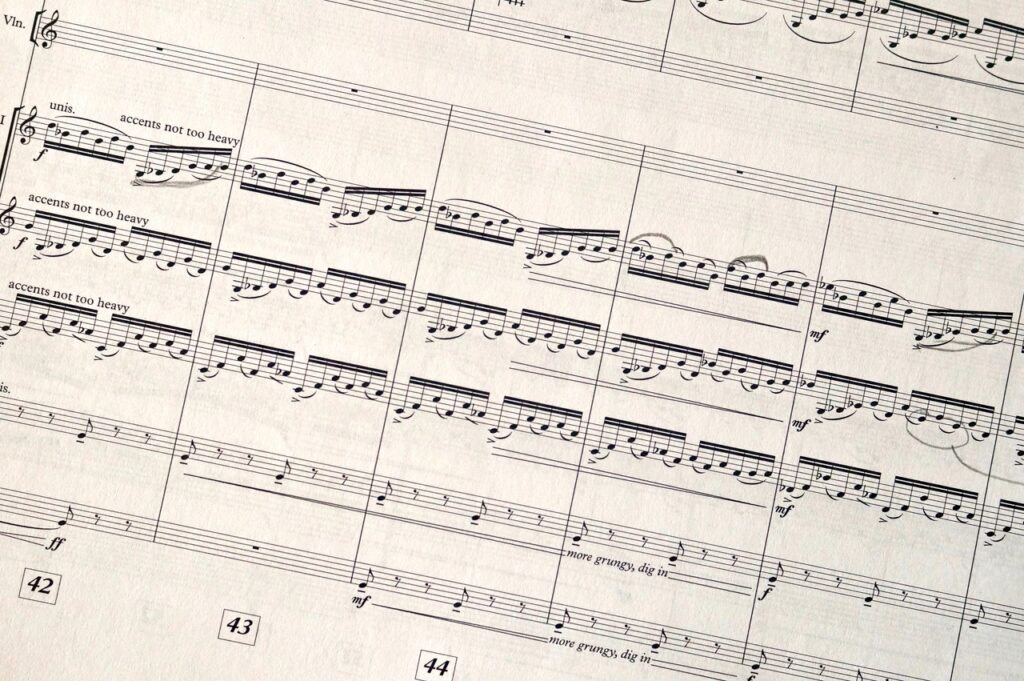

But even with all of this information, composing a score is still a lot of guesswork. At the same time that I’m euphorically throwing notes on a page, I am also essentially attempting to mind-read, to figure out what soundtrack the director is playing in his or her head. At some point, you (Mr. or Ms. Director) are going to be listening to the music I’ve written, and while you recognize it’s not working for you, you don’t know why. These tips can help:

- You can never have enough adjectives.

I don’t mean use a thesaurus. I just mean use as many different descriptions as possible to explain the emotion you want, to avoid adjective ambiguity. “Fun” can mean all sorts of things. Is it “fun” like comical? Or is it “fun” like out-on-the-town young adults partying? Those are two very different types of fun and would have completely different scores. It’s especially helpful to switch the adjectives you’re using when the composer gives you version after version of the wrong type of music. Telling the composer, “it needs to be even more fun” after each version, isn’t going to get you sexy cocktail fun if the composer is thinking fart joke fun. Try to use more adjectives to describe the same emotion in different ways.

- Recognize what to keep.

Getting the right sound usually takes at least a few different tries (in some cases…several). Sometimes, I will have to start version 2 completely over from scratch, but other times, I only have to make small (or large) adjustments on the current music to get it where it needs to be. But I can’t tell you how many times I’ve gotten comments on a scene from the director, and completely started over from scratch for the next version, only for the director to then say, “oh, I actually liked the previous version.” If there is any part of the music that is working, please say so! This can save a lot of time and a lot of failed versions. A good composer will also be trying to figure out what to keep and what to change, but it helps and makes things quicker if the director is also thinking along these lines. So, if you receive a cue that is on the right track but needs adjusting, try this:

“This is on the right track, but needs adjusting…”

“I like this, but can we tweak these things…”

“Let’s continue this way, but can it be more…”

Those kind of phrases will cue the composer that they don’t need to start from scratch. (And the opposite is helpful for when the composer has completely missed the mark. “It’s not what I was envisioning…” “Can we start over and try this….” are the types of phrases that will clue us in to a complete redo of the cue.)

You might be asking yourself, “how will I possibly be able to describe what is working and what needs tweaking?” The answer is in Tip #3.

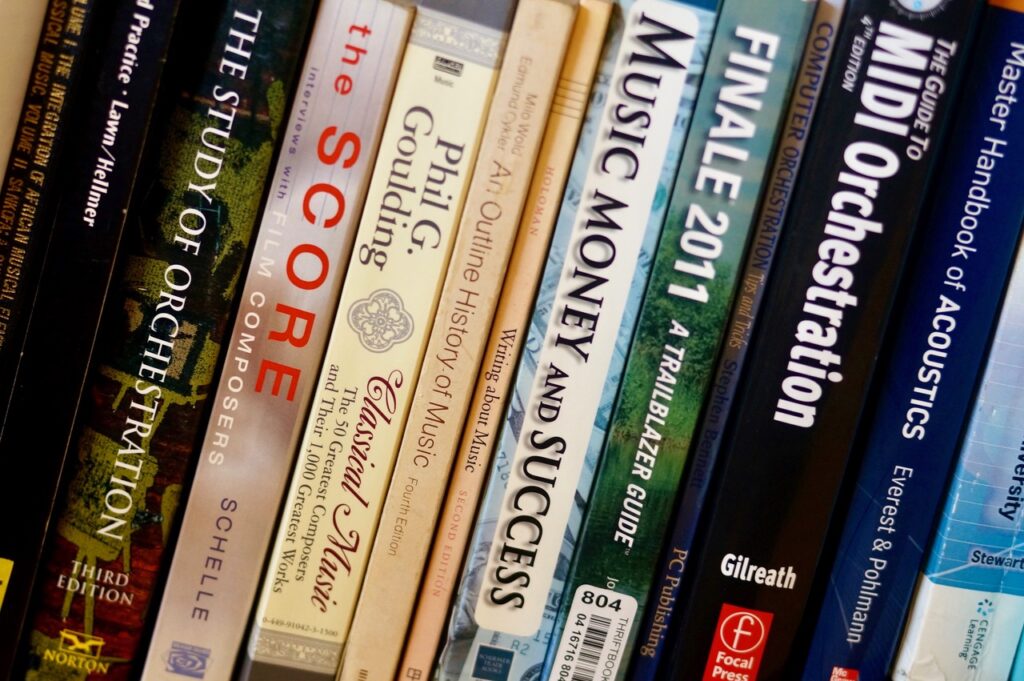

- Know a few generic musical terms on which you and your composer can build a language.

The ones below are very basic, and probably the ones you will need the most.

Melody – A melody is the tune you hum in the shower. It is generally single notes in a row, moving through time linearly.

Chords – In simple terms, chords are multiple pitches that are happening at the same time. Often, a melody will be floating on top of the chords. The chords are the accompaniment. A Chord Progression is exactly what is sounds like: the progression or succession of chords happening one after another. Unless the music is using a lot of sustained notes, it most likely has some sort of chord progression.

Pitches – If melody and chords are too confusing, then just use Pitches. Does everything else feel right but you’re just not fond of the actual notes that the orchestra is playing? Those are the pitches.

Tone – Generally refers to the emotions that the music makes you feel. Happy. Sad. Dark. Foreboding. Etc.

Texture – This is a more practical term about the building blocks of music. How many instruments are playing (one solo, or a whole orchestra), how many different parts there are (a simple sustained note, or fast chords one right after another), the complexity or simplicity of how all the parts fit together, etc.

Volume – Hopefully you know that this means how loud or soft the music is. But volume can have a surprising impact on how the cue lays with the scene. Composers will write the music at a regular volume, knowing that it will be turned down in the final mix. Does the music stick out too much? Try turning it down and see if that fixes the problem.

Pacing – Essentially how fast the music is.

Simple – OK, now we’re getting into terms that are more ambiguous. Simple can refer to the texture (e.g., how many notes or melodies are playing at the same time), or it can refer to the pitches (i.e., standard/conventional chords and melodies vs. chords and melodies that have a lot more notes and dissonances). It could also refer to pacing. If you want something simpler, you might want it slower.

Complex – Same but opposite. Complexity can refer to a texture of overlapping melodies, (“a lot going on,”) or it can refer to very intricate and unconventional chords.

Thin – This most often refers to texture. A thin texture does not have a lot of different things happening at the same time, and usually not a lot of different instruments.

Dramatic – This often refers to performance. If something is “too dramatic,” maybe it’s too big for the scene, too many volume contrasts in too short a time, maybe the performers are playing with too much expression, etc.

I will add to this list as things come up in my experience. But don’t worry. You don’t have to actively add these words into your vocabulary. They will naturally come up by either you or the composer, and having a basic grasp of the meanings can be helpful.

If you would like an example of some of these terms, click this link which will take you to a piece that I wrote for piano. If you listen to the first 15 seconds of Movement 1, this is what you will hear:

- A chord progression (several chords played one right after another)

- The chords are complex (unconventional, a lot of pitches and dissonances).

- The texture is simple. (There is only solo piano, and there is nothing else going on besides the chords.)

- I would call the tone stately, and dramatic. (It’s quite a big gesture for just the piano alone.)

- Use temp as a conversation tool.

Ah, the dreaded temp. (For the non-musical, non-directorical people reading this blog, temp refers to “temporary music,” which is music from other movies or sources that is placed in the film to help get a feeling of what the film will be like with music.) Most of the film composers I know abhor temp. If you can manage it, try showing your composer the film at least once through first without any temp. He or she will appreciate it.

However, I am one of the strange-but-true composers that actually likes temp. It does such a good job of telling me what the director is envisioning! Without saying any words at all, I can pick out what sort of tone, texture, pacing, and complexity that you’re looking for. But temp music comes with a few very nasty downsides:

- It’s not going to be perfect for your film because it wasn’t written for your film.

- It could influence the composer in ways you don’t want it to.

- YOU CAN’T USE IT! (because it’s copyrighted by someone else)

So here is what you can do to use temp as a conversational tool, rather than as a crutch:

- Make sure to tell the composer what you like about the temp, and especially what you DISLIKE about the temp, or what is lacking in the temp. As I mentioned above, composing for a director is complete mindreading. So if I know exactly what about the temp you like and dislike, I can hone in on the sound you’re going for that much faster.

- Use multiple temp music pieces for the same scene! You don’t even have to align it with the film. Just send your composer a bunch of youtube links to different pieces of music within that same style. This is the single greatest communication tool you can possibly give your composer. If I am given three different music pieces that are all in line with the sound you want, I can effortlessly pick out the elements in each of those pieces that are the same, and then know exactly what vibe you want, without having one temp in my head, overshadowing everything I compose. Essentially this helps me to be creative and come up with something unique, but that still will have the elements that you’re looking for.

- Use the temp once or twice if you have to, but then NEVER LISTEN TO IT AGAIN (as absolutely as much as you can manage). Because the one, true, abominable thing about temp that all composers fear, is: Temp Love, when the director falls in love with the temp music, and can’t imagine anything else. This is where the composer hears those dreaded words, “Can you make it more like the temp?” over and over and over again. Using a score that is exactly like your temp hurts your film for two reasons (but really the same reason twice):

- Your film is now ripping off music from other films.

- Your film now lacks its own unique sound.

Neither the composer or you want a complete rip-off of music that already exists. It dulls the film. It makes it exactly like a million other films out there. The goal is to come up with something so new, and fresh, that people can’t look away. And a musical score unique to your film, that no one has heard before, creating a whole new sound world for your film, is one of these vital elements. (I don’t mean it’s better to have some crazy out-there score, or that the music can’t be in the same style as other film scores you love! Just something that has been personally fitted and written for your film is automatically going to be more exceptional.)

Before moving on I would like to recognize that Temp Love can sometimes be unavoidable, and express my gratitude for the directors I’ve worked with that are able to recognize it in themselves, and work with me to uncover a medium ground.

- Pull in the composer early!!

It’s easy to develop Temp Love if you’ve cut and edited your film to the temp music and watched it with the temp music 100 times. You have creatively and artistically invested yourself in the temp music. So why not creatively and artistically invest yourself in music that was written specifically for your film? The picture does not need to be locked. (In fact, it’s not even a necessity for there to be picture at all! Though composers do lean on the picture for inspiration, there’s no rule saying that the picture must come first.) This gives the composer much more time to come up with that unique sound for your film, to be creative, and above all to not be rushed into sloppiness, and it can also serve as an inspiration for you! It’s a win-win for everyone. With the bonus of avoiding the inevitable breakup with your temp.

If you have any questions or comments about this article, don’t hesitate to contact me!